“Framings”

Curatorial Statement by Katherine Behar

DOWNLOAD CURATORIAL STATEMENT (.PDF)

There is a center

but the center is empty.

—Lydia Davis, “The Center of the Story” (quoted in Gabriela Vainsencher's Negative Capability)

The New Media Artspace is proud to present Gabriela Vainsencher: Inheritance, a solo exhibition of single-channel videos alongside sculptural and photographic media. Inheritance brings together four video works created between 2014 and 2016 (exhibited in-person and online), in particular one created through dialog with her mother. These works are accompanied by details of one of Vainsencher's large-scale ceramic works from 2021 (exhibited online only) created after she became a mother herself, as well as artifacts of her practice (exhibited in-person only), including ceramics and photographic props that appear in the videos and provide context for these works. The exhibition sets a frame for understanding Vainsencher's work over this span of several years, and that work in turn is enframed by her experiences being Jewish, Israeli, Argentine, trilingual, an immigrant—and no less, being a daughter and a mother.

Emerging from this intersectional inherited identity, Vainsencher's feminist artistic practice highlights learning as a non-hierarchical collective process. This extends to an emphasis on community, on text and commentary such as the Talmudic practice of framing a text with other texts, and on learning from one's elders and learning together, all of which Vainsencher attributes to Jewish traditions. Vainsencher's creative process revolves around dialog, textual commentary, and collaboration. In turn, this “revolving” is literalized in the forms of her videos and sculptures, which are continually circling around, looping, swerving, turning, and not quite returning. From speech comes stutters, from touch comes porosity, from openings come closures, from surfaces come circularity, from daughters come mothers. Vainsencher's works are always coming around again with layered meanings, which the artist holds open to make space for interpretation and transformation.

Negative Capability begins with a shot of the upper torso of a woman (the artist) wearing a black shirt and nearly disappearing against a black background. Her hands and throat, exposed above the neckline and below the sleeves or her garment, are the only parts of her body that are visible against the black void. Also visible is an object, a cylindrical ceramic sculpture, which she holds with both hands in front of her chest at the dead center of the frame. She rotates this object aiming its mouth at the camera, and in sync the video image moves in and out of focus, as though by manipulating the hollow sculpture she controls the focal ring on the lens. After a few turns, an older woman's voice commences a one-sided conversation, speaking in Hebrew which at times gives way to Spanish, while white subtitles in English pop up in staccato rhythms of short phrases usually offset toward the bottom or sides of the frame. The cryptic narration mixes anecdotes, metaphors, humor, and wisdom. Generally, it seems to concern coming to terms with what isn't known or knowable, what may or may not happen. Eventually it becomes evident that the narrator is discussing her practice as a psychoanalyst.

Like talk therapy itself, once it begins the voice doesn't stop. Instead, the image shifts: hands, always doing, manipulate rolling and sliding abstract ceramic forms; a throat swallows; the figure hides behind masks; more cylindrical forms rotate around her missing head, obscuring it; hands attempt to piece two ceramic fragments together to form a circle, but the gaps are too wide to close its loop and any way she turns the fragments spans only half the curve.

Eventually the narrator explains the meaning of the phrase “negative capability,” a concept introduced by the poet Keats to refer to “the ability to be suspended in not knowing, … not having closure … not doing.” The narrator praises this difficult work of keeping things unknown, not rushing to closure. Finally, after the figure disappears and against an image of undulating waves, comes a question from the narrator, the artist's mother, who asks “What's this all about Gabriela?” and then—like the analyst she is—begins to speculate as to her daughter's motivations, but—like the mother she is—with laughter.

On one level, Negative Capability explores intergenerational communication and miscommunication. The psychoanalyst mother works in her medium—talking and words—while the artist daughter works in her medium—images and objects. The two parts never quite align in form; yet, in content they are in uncannily perfect alignment. This is because on another level, the piece compares how mother and daughter both contend with something similar in the different work they do. Both engage a process. Both allow space for an empty center—the unknown that must be held in abeyance to keep a process—whether creative or therapeutic—richly alive. Vainsencher has written about the how analysis and art share an investment in interpretation.1 For each, the empty center holds an elusive meaning that can't be arrived at or even articulated, or else the artwork would be trite, or else the self-realization would be too pat, or worse externalized (as the mother points out in her first lines).

Negative Capability originated in audio recordings of phone conversations between the artist and her mother, which she first painstakingly transcribed, then translated, then remixed. Only at the last step did she abandon her devotion to faithfully conveying her mother's words. In this artfully (re)interpreted conversation with her mother, Vainsencher emphasizes a process giving rise to a collectively authored frame circling an unknown, which she likens to the Gamra page in Talmudic traditions. At the center of a Gamra page sits holy text, and enframing that text are other texts consisting in mutable commentary. In the case of Negative Capability, the mother's text lies at the center, and the framing commentary, open to interpretation, is the artwork that emerges from the daughter's reworking. This encircling processing of a holy or wholly unknowable connects psychoanalytic process and artistic process, as both attempt to apprehend something intangible at their heart.

The complementarity of two disciplines in Negative Capability is explored figuratively in the next video, Duet, which features another collaborator of Vainsencher's, the dancer and choreographer Leslie Satin. Satin faces the camera with the tight frame grazing her forehead and chin. Her face is in slow but constant motion. As she moves her head side to side, like indicating a silent “no,” the camera swivels on a tripod, mimicking her movement. The duet unfolds as parallel movements between the discipline of performance represented by Satin, and the discipline of video, represented by Vainsencher's camera.

In this duet, the empty center is where the dancer's gaze and the gaze of the lens intersect. Continuing the themes of Negative Capability, Satin's solemn refusal suggests a negation, while both the shaking head and the panning camera follow the arc of a semicircle. Combined, the two might make a complete circle, but instead they draw attention to the empty space between the performer and the lens. The simple eloquence of Duet is to hold empty that space between them, which is Vainsencher's invitation for the viewer to fill in their own experience.2 Vainsencher's intention is to make room for the viewer, which she understand requires an artist not take up all of the space herself, burdening an artwork with overprescribed meaning. Following the garrulous Negative Capability, this silent video might even be interpreted as its inverse. Whereas Vainsencher's mother only speaks and never appears in Negative Capability, Satin's face embodies the frame as she shakes her head “no” in a refusal to speak.

Satin appears again in Leslie Across the Floor. Again, much as Negative Capability locates a common ground between artistic and psychoanalytic process, Leslie Across the Floor explores a feature in common between the two collaborators' disciplines, video and dance. Both utilize entrances and exits and the choreography of this video is reduced to exactly that. Satin enters from the left side of the frame, inchworming on her back along the floor until she exits at the frame's right side. Unlike Duets which focuses exclusively on Satin's face, here her head is turned away from the camera so that her face is never visible. The movement of her body is exaggerated by foley audio which unexpectedly substitutes the sound of dragging heavy metal in place of the softer sounds of cloth and flesh on floor.

Entrances and exits, and the anticipation they entail, are performed again in the last video, Here It Comes but this time the performer is the ocean. Recalling the final watery image of Negative Capability, this video shows waves lapping against a coast. As the waves slowly roll in, choruses of whispers repeat “Here it comes” overlapping with “It's coming.” Just as the ocean's waves never stop, the anticipation never reaches a conclusion. Instead, this video holds our attention, like the voices hold their breath and gasp for air. The empty center of Here It Comes is that which might come, which might fill in what's missing from an evacuated center constantly being washed away, sucked back to sea like the vacuumed void of undertow.

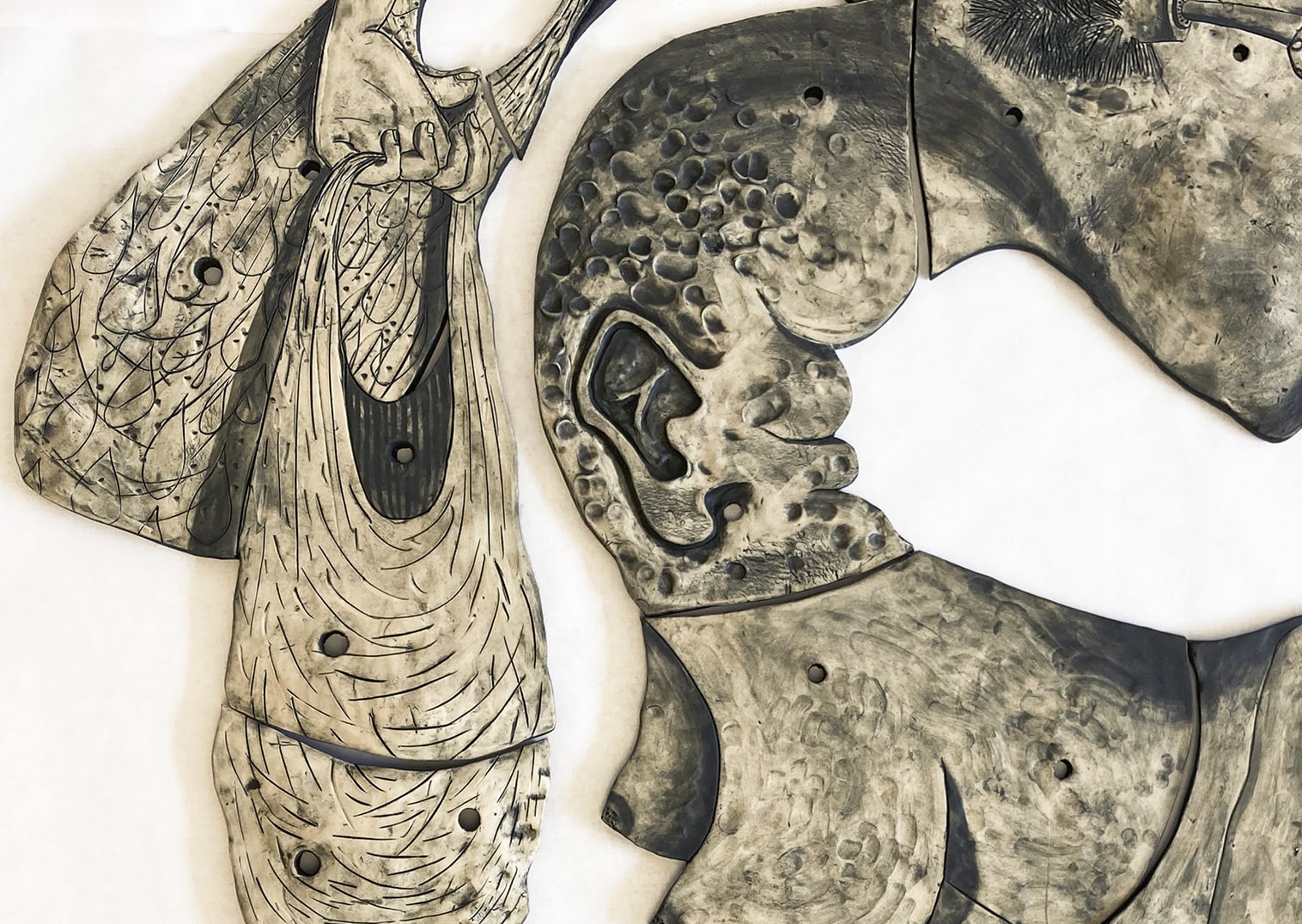

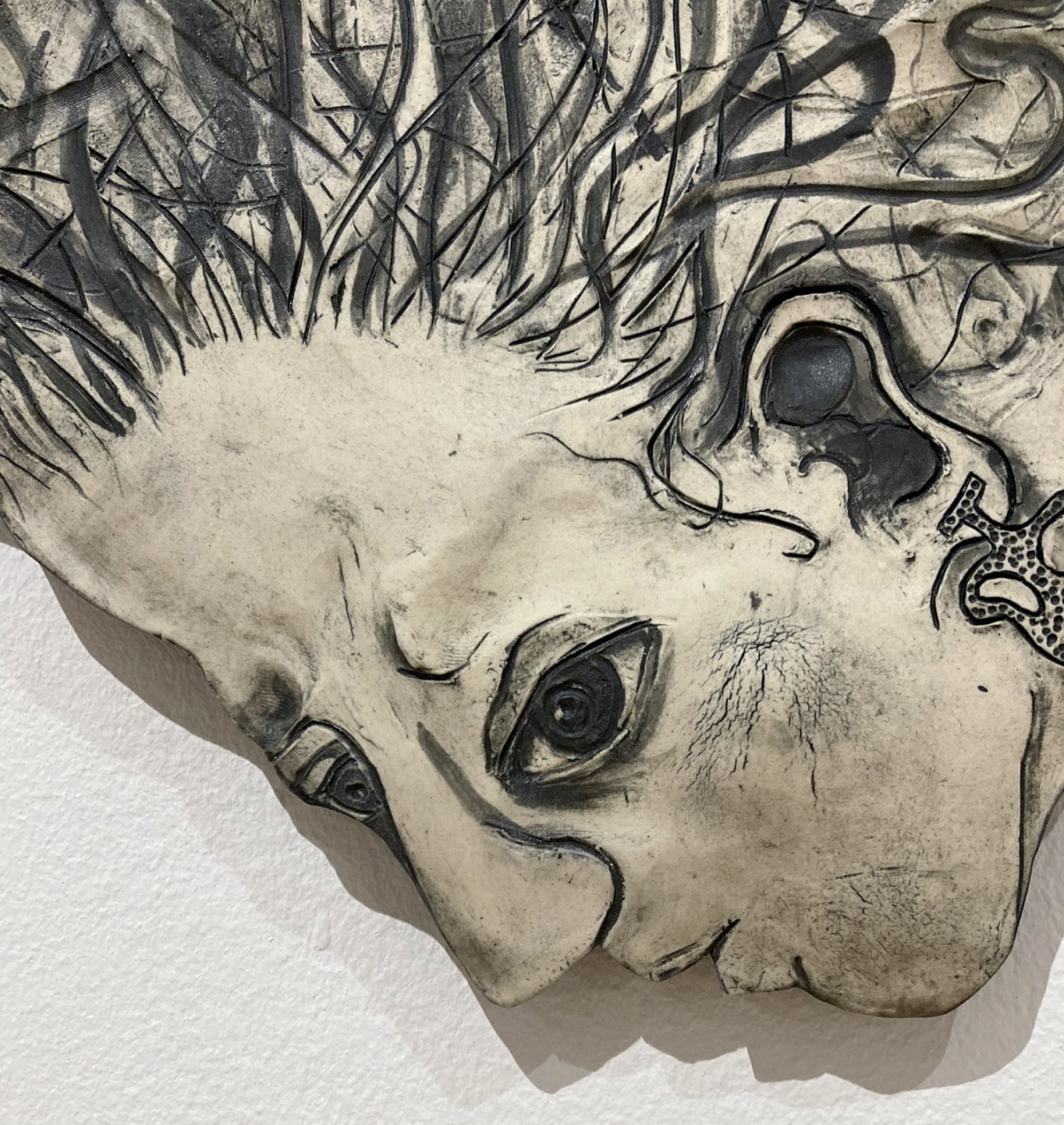

In the online version of the exhibition, each video is bordered by close detail images from one of Vainsencher's largescale ceramic works, Mom. The sculpture itself is a wall-scaled relief work showing a twisting looping, many-limbed figure. Created after the birth of Vainsencher's first child, Mom shows the many roles she takes on as a daughter turned mother to a daughter. As though pulled in many directions, the clay surface bears the touch of a million clamoring fingerprints. The deeply textured surfaces recall the busy hands manipulating clay objects in Negative Capability. In Mom, hands are also constantly doing things, now cooking, shampooing, and carrying. In Inheritance, the textures of Mom mimic the enframing form of the Gamra page, also becoming a frame for the video works Vainsencher created as her mother's daughter.

Many of the works in the exhibition take the visual shape of a frame: from the hollow ceramic cylinders and circles in Negative Capability, to the panning semi-circle arcs gestured in Duet, to the bracketing device of entrances and exits that motivate Leslie Across the Floor, to the anticipation that holds attention in Here It Comes, to the curatorial decision to use the textures of Mom as a border around video works. These enframing forms make reference to the Talmud which inspires the design of the Inheritance exhibition. They also function much like a family does—they encircle, enshrine, and protect something precious at the center.

Vainsencher is also inspired by the Jewish practice of learning together, Be'Tzavta, which she loosely translates as “as a team; together.” Be'Tzavta involves reading as a group and discussing a text while seated together in a circle, a practiced she was introduced to by the artist Ofri Cnaani's feminist reading group at AIR gallery. Once again, “there is a center but the center is empty.” Vainsencher consciously connects Be'Tzavta to the anti-hierarchical feminist approaches she applies throughout her work. At Baruch, she will present a special participatory performance of Here It Comes that literally embodies Be'Tzavta circular communal form. Additionally, at the New Media Artspace in-person exhibition, she shares several of the artifacts and process pieces that contribute to her work, inviting viewers into her process by creating an intimate learning community in the Newman Library. Mirroring the Gamra page and the Be'Tzavta practices, encircling text and (re)interpretive commentary underpin Vainsencher's process at every level. In Inheritance, these are continually come around, revolving and enframing through the artist's reinventions, reincarnations, and inheritances.

This exhibition is generously sponsored by the Sandra Kahn Wasserman Jewish Studies Center under the directorship of Dean Jessica Lang.

Gabriela Vainsencher: Inheritance is curated by Katherine Behar, Professor in the Fine and Performing Arts Department in the Weissman School of Arts and Sciences, Baruch College, CUNY and is produced by the New Media Artspace Student Docent Team. The exhibition is made possible by further support from the Baruch Computing and Technology Center (BCTC), the Weissman School of Arts and Sciences, and the Newman Library. All images appear courtesy of the artist.

Gabriela Vainsencher was born in Buenos Aires, raised in Tel Aviv, and currently lives in Montclair. She received her MFA from Hunter College, CUNY in 2016. Past solo and two-person exhibitions include Asya Geisberg gallery (solo) CRUSH Curatorial gallery, NY, NY, A.I.R. Gallery, Brooklyn, NY (solo), Hanina Gallery, Tel Aviv, Israel; Musée d'Art Moderne André Malraux, Le Havre, France; Parker's Box Gallery, Brooklyn, NY and La Chambre Blanche, Québec City, Canada (solo).

Her work has been included in group exhibitions including Marisa Newman Projects, NY, NY, Bergamo Modern and Contemporary Art, Italy; Kunstforening, Tromsø, Norway; Pierogi gallery, Brooklyn, NY, The Freies Museum, Berlin and The National Gallery of Saskatchewan, Canada. Residencies include Yaddo, The Atlantic Center for the Arts, Byrdcliffe Artist Residency, Woodstock (USA), Triangle Arts Association (France), and La Chambre Blanche (Canada).

Vainsencher is the founder of the Morning Drawing Residency. Her writings about art have appeard in Hyperallergic, Title Magazine, and Tohu magazine. She occasionally teaches art at Williams College, and the Macaulay Honors College at Hunter College, CUNY.

[1] Gabriela Vainsencher, “Negative Capability,” Master of Fine Arts Thesis (Hunter College of the City University of New York, 2016).

[2] Gabriela Vainsencher, interviewed by the author, online, July 5, 2023.

Gabriela Vainsencher speaks with Silvia Ruzanka

This year the New Media Artspace presents two solo exhibitions by Gabriela Vainsencher and Silvia Ruzanka. Each addresses process from an expanded perspective, extending from artistic and psychoanalytical processes to botanical and computational processes. In conjunction with Vainsencher's exhibition, Ruzanka interviews Vainsencher as the first part of a two-way dialogue between the artists on their works in relation to these and more ideas.

Silvia Ruzanka: Watching Negative Capability and thinking of what question to begin with, that archetypal psychoanalysis question almost seems appropriate: tell me about your mother. You talk about connections between her work as a psychoanalyst and your work as an artist. Was that something you discovered in the process of making that piece?

Gabriela Vainsencher: I was always fascinated with my mother's work and the way it informed how she sees the world. Growing up, psychoanalytical theory was not a remote academic subject. It was sayings peppered into everyday conversations, the lens through which people and situations were discussed. It was only when I started being exposed to Freud as an undergraduate that I realized there was an external source for these models: they were not all my mom's ideas! I then started asking her more about her work and she told me about people like Melanie Klein, Wilfred Bion, and Donald Winnicott.

When I started working on the recordings that would become Negative Capability, the first thing I asked her was to explain to me what an interpretation was. To me, this is the most mysterious part of the psychoanalytic process, and the one closest to artistic inspiration. It is the moment in which the analyst creates something with and for the patient. It's something that was not there before, and yet it is connected to everything that was said (and not said) previous to its creation. It parallels in this way the creative process, in which there is a sequence, a progression of ideas and methods, but the real magical moments in art are the ones in which this progression suddenly births something completely new—an image, an idea, a way of seeing the world that both is connected to the artist's practice, but also is new and unexpected by the artist.

SR: One of the threads I see in your work is the cyclical nature of things: beginnings and ends, undulations, repetition that returns but always with variation. (I have a fascination with the Möebius strip, a shape that's cyclic but turns in on itself.) I'm interested in how you think about these cyclical patterns, the motions of the body, motions of the waves, cycles of everyday activities?

GV: My interest in cycles is connected to feminism and the postmodern rejection of art history as a linear progression. And personally, I don't believe in progression of any sort in a straight line. My growth as a person and as an artist has always been in loops—I end up back where I was, but this time I am myself a little bit changed, and so I find myself in a different position.

SR: With ceramics there's often an association with a finished product and with a kind of permanence. In your work there's an emphasis on process, on open-ended, unfinished states. How do you think about ceramics in these pieces? Do they create a kind of tension? Or do you see ceramics differently?

GV: What I love most about clay is how it starts its life as the most malleable, most changeable material, and ends up one of the most permanent ones. When I work with clay I try to stay very connected to its potential for change, for capturing fleeting moments like a finger's impression, a drawn line pressed into it, a wrinkle. All the while, I know that once it goes in the kiln, it is likely to outlive anything else I produce by thousands of years. I also enjoy how cheap clay is. I have a hard time working with expensive materials. They feel finished somehow, before I've touched them. Clay is dirt, it means nothing and costs very little, and gives me the freedom to waste it, which for me is very necessary for my creative process.

SR: Mom resonates with me in a number of ways, in the imagery and in some of my own experience. I'm interested in your thoughts and experience of motherhood, across different cultures and particularly through the lens of the pandemic.

GV: When I became a mother, I experienced a profound shift in identity from one that was centered around being someone's daughter to being someone's mother. This shifted the way I perceived myself in time—suddenly I was no longer an endpoint, but a passageway into the future. This is a very common thing to realize; it happens to anyone that creates another generation. But it's nonetheless a powerful force, which affected not only how I planned my life (meaning, I started planning my life rather than just living it), but also profoundly changed my work.

I made Mom when my daughter was two years old, about a year into the pandemic. It is a self-portrait as a mother, depicted while doing a lot of tasks that have nothing to do with being an artist. But of course, as I was making it I was in the studio, finally, after having been forced into being a stay at home mom and not having a studio for over a year. It was the largest sculpture I had ever made. It took many months and meticulous planning and patience—skills motherhood had taught me. The pandemic was a difficult time to be a mother, but being a mother also saved my sanity during it. It forced me to laugh every day, to have hope. I am writing this text in the first week of the war in Israel—where I grew up and where my parents and many friends are. Again, I have a young child—I gave birth to our son almost three months ago. Caring for him and for our daughter is what keeps me hopeful, what forces me to look away from the harrowing news and into the sunshine, to go to the studio and make art and hope for a better future for my kids.