Curatorial Statement

Katherine Behar

The New Media Artspace is pleased to present kate-hers RHEE: Inventing Genealogies, an interactive online exhibition that confronts and problematizes Asian American and diasporic transnational identity. In common

usage, “genealogy” refers to accounts of ancestral descent.1 But for the transnational artist kate-hers RHEE (이미래/李未來), genealogy is invention.

The stakes are high when RHEE repositions genealogy this way, because genealogy frequently invokes DNA and other technologies that secure individuals’ legal rights through patriarchal constructs of lineage, birth, and

bloodlines. As a transracial adopted Korean person, RHEE discovered that her family tree was a fabrication created by the South Korean government when she was a small child to falsely construe her as an orphan and thereby expedite

expatriating her from Korea to the United States. To claim her own identity and rights without the benefit of a conventional (or factual) family tree, RHEE embarks on inventing genealogies, a process filled with twists and turns and

difficult choices, which this exhibition illuminates.

Foregrounding choice, Inventing Genealogies replaces a deterministic genealogical account of RHEE’s identity with a choose your own adventure-style narrative that offers as many paths untaken as paths forward. The

online exhibition design, created by the New Media Artspace Student Docent Team, is inspired by family trees and DNA. Plunging through tree rings of a family tree made of documents, viewers tunnel through bureaucratic paperwork as they

choose a path linking different artworks. At each work, viewers can interact to descramble an appendix that offers commentary about the project, alluding to the process of learning to communicate as a non-native speaker, and the idea of

so-called “broken languages.” Meanwhile, viewers track their progress through the exhibition through a mini map that resembles a DNA double helix. By uprooting the family tree as a concept in itself, Inventing Genealogies

explores what happens when identity and rights aren’t mere matters of inheritance.

In a recent Instagram post introducing herself and her interdisciplinary practice to her followers, RHEE recalls being “literally cut off from [her] ethnic identity as an ‘orphan’ and sent away to be adopted transracially as a

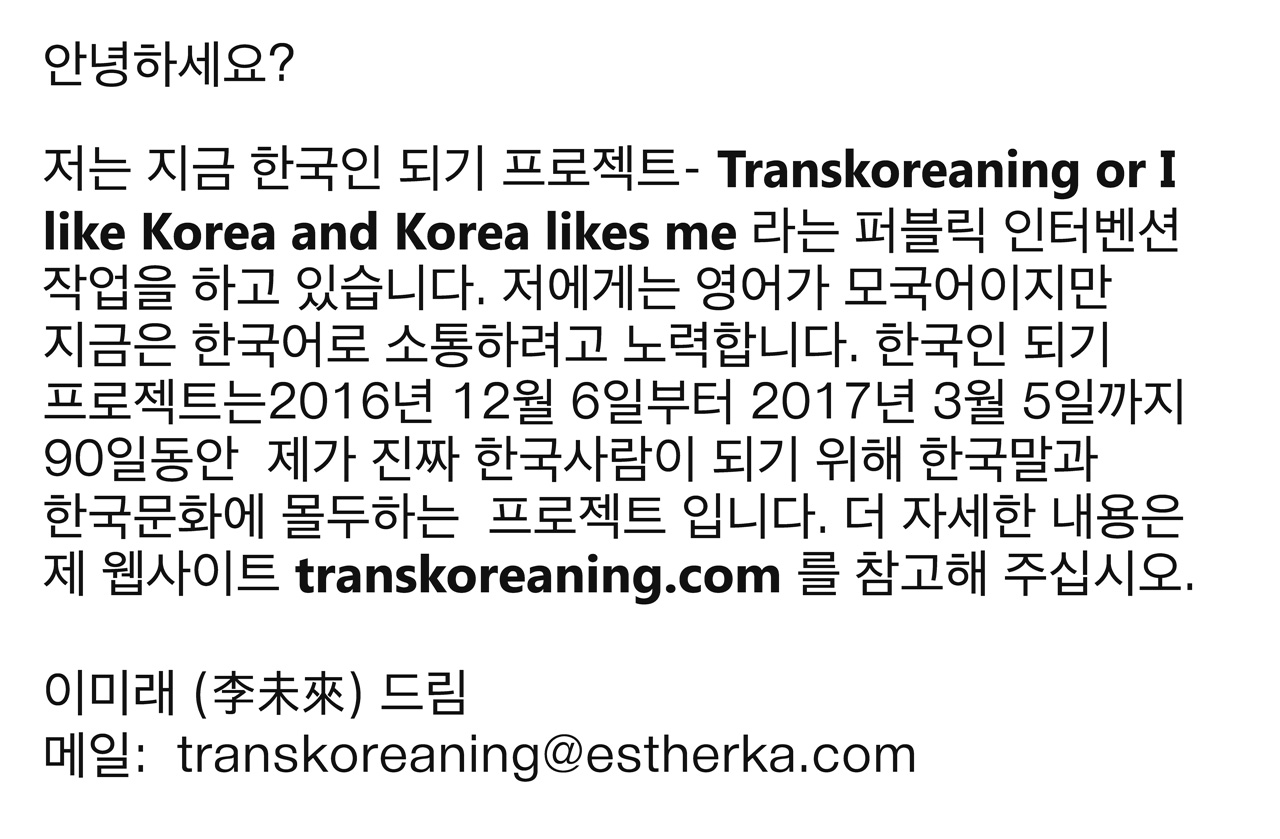

survivor of #genderbiasedsexselection abandonment.”2 Grappling with this experience, the works in Inventing Genealogies are derived from the largescale ongoing project that emerged. In 2016–2017, RHEE moved to South

Korea for 90 days as part of a durational lived performance called Transkoreaning, in which she aimed to become “authentically Korean” (in scare quotes), a process she documented on social media, through accruing massive amounts of

legal paperwork, and in a resulting body of artworks using these materials. In her words, the initial goal of Transkoreaning was “to become Korean in every way possible in language, culture, traditions, customs, and mannerism by

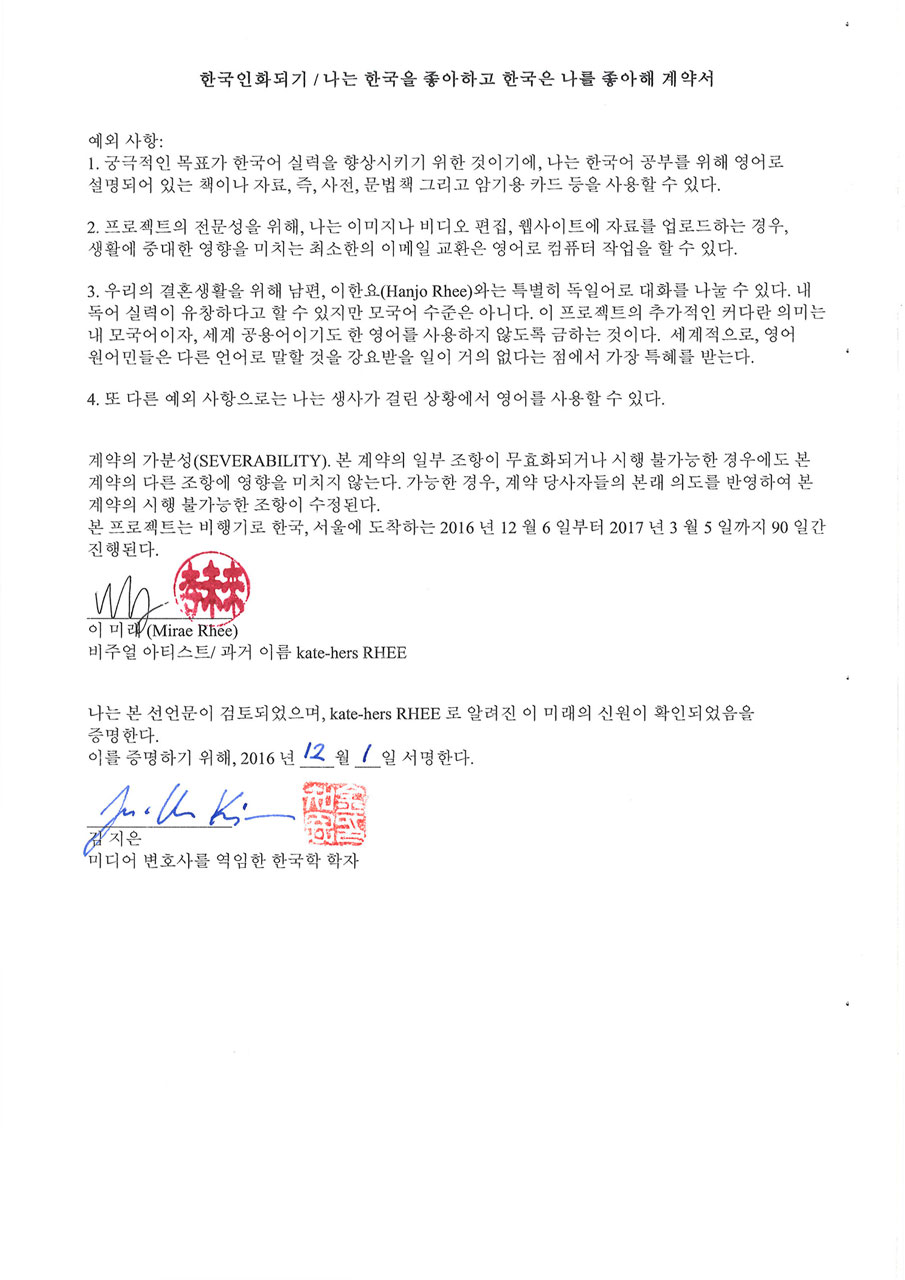

immersing myself as a full time Korean.”3 Among other things, RHEE signed a contract with herself to communicate only in Korean, despite having limited experience with the language. As the project continued, RHEE sought and

obtained South Korean citizenship and endeavored to legally change her name to a chosen Korean name, Mirae Rhee, an ongoing legal process which RHEE explores in the final work in this exhibition. Equal parts bureaucratic paper wrangling and

public code switching, Transkoreaning involved “changing her cultural presentation to accord with her outside sense of her ethnicity—the idea of what it means to be an ethnic and cultural Korean woman.”4

If in RHEE’s artwork, genealogy is a matter of choice, it is something she opts into performatively, rather than a foregone conclusion. Treating genealogy this way emphasizes solidarities with queer theory and critical race

theory. RHEE’s approach corresponds with queer theorists like Judith Butler’s understanding of gender identity as performed, and with the notion developed by critical race theorists like David Theo Goldberg, as well as contemporary biology,

that race is not a biological category. Indeed, while RHEE considers her attempts to performatively choose her cultural presentation in Transkoreaning a “spectacular failure,” she also calls it an “earnest search for authentic

self.”5 As such, she respectfully engages the prefix “trans-” to help herself understand her own experiences of “ethnic dysphoria.” For example, she seeks critical intersections with queer culture’s different but parallel modes

of drag, coming out, passing, and transitioning. RHEE contrasts her conscious decision to turn toward and learn from other Others with the headline-grabbing controversy surrounding Rachel Dolezal, a white woman living as a Black woman who,

comparing herself to the transgender community, called herself “transracial.” As RHEE notes, Dolezal appeared unaware that the term “transracial” had an established meaning among the transracially adopted community, who have long used the

term in their academic and political work to self-define themselves as being adopted and raised by families across race and ethnicity.6

In Inventing Genealogies, visitors embark on a journey faced by quotations from two Black thinkers, Malcolm X and Trevor Noah, concerning the racialization of Asians. Taken together, these two quotations illustrate

“racial triangulation,” a theory formulated by Asian American Studies scholar Claire Jean Kim, which RHEE identifies as a source of inspiration for many of her projects.7 For Kim, the cultural construction of racialization occurs

in a “field of racial positions,” always in relation to other races, which “are in fact mutually constitutive of each other.” Kim convincingly argues that “Asian Americans have not been racialized in a vacuum, isolated from other groups; to

the contrary, Asian Americans have been racialized relative to and through interactions with Whites and Blacks. As such, the respective racialization trajectories of these groups are profoundly interrelated.”8 After choosing one

of the two quotations, visitors proceed on diverging paths, through which they can view related works. These include photographs and videos, RHEE’s contracts with herself, confessional diaries, Instagram posts, an overwhelming archive of

paperwork that ushered her passage from East to West as a child and again from West to East as an adult, and finally, her name change.

While this exhibition hews to the process of Transkoreaning, and retraces RHEE’s steps, it must also account for the steps not taken, the decisions not chosen, the lives not lived. If genealogy is a matter of

inventive choice, then it is no longer something that can be “accurately” reverse-engineered. As though in compensation for this dilemma, Inventing Genealogies includes subsidiary texts, which RHEE calls “appendixes,” that

supplement and explain the works. On the one hand, these appendixes flesh out the emergent narrative, much as appendixes in books provide further context to a story. But in books, appendixes themselves are no more than side bars or dead

ends. So, on the other hand, these appendixes that flesh out are fleshy themselves, like an anatomical appendix. In a Western medicine approach, which views “organs as separate entities,” surgically removable in cases of sickness, the

appendix is “an organ that is supposedly ‘useless.’”9 This view contrasts with the approaches of Eastern medicine, which stress holism, interrelation, and interdependent consequence—all of which are guiding principles for

Inventing Genealogies.

Each major decision that RHEE made in her attempt to “become authentically Korean” is punctuated by an artwork that uses the archival and artistic material she generated throughout her months-long performance. Likewise, each

artwork serves as a decision tree point for visitors navigating the exhibition website. At times, the intersecting paths converge at common decision points marked by critical artworks, like the crisscrosses of a double helix of DNA that

appear to double back toward each other when viewed frontally. Even so, Inventing Genealogies shows that going backward and forward are far from equivalent and hardly exchangeable. Indeed, RHEE’s ambitious undertaking to travel

West to East to South Korea to regain the South Korean citizenship she was denied, does not in any way remedy the trauma of her passage from East to West as a child, and the life paths that unfolded from that initial journey. These twinned

passages do not cancel one another out. Rather, Transkoreaning is another choice in RHEE’s own adventure—an ongoing exploration of what she calls “transnational identity, integration, and the self as Other.”10

To this end, the exhibition concludes with RHEE’s newest work, The Corean, a project that explores her name change. RHEE’s name has changed four times throughout her life and the process remains

incomplete.11 It is significant,

then, that the Chinese characters for her most recently chosen name, Mirae (未來) mean future, a reference to her future self. Thus, with this work, even as the exhibition concludes, RHEE’s journey of conscious choice and

self-determination continues.

This exhibition is generously sponsored by the Sandra Kahn Wasserman Jewish Studies Center under the co-directorship of Professors Jessica Lang and Andrew Sloin.

kate-hers RHEE: Inventing Genealogies is curated by Katherine Behar, Associate Professor in the Fine and Performing Arts Department in the Weissman School of Arts and Sciences, Baruch College, CUNY and is produced by the New Media

Artspace Student Docent Team. The exhibition is made possible further by support from the Baruch Computing and Technology Center (BCTC), the Weissman School of Arts and Sciences, and the Newman Library. All images appear courtesy of the

artist.

Artist Bio

Transnational feminist kate-hers RHEE (이미래/李未來) is an interdisciplinary visual, performance and social practice artist, who works between Germany, South Korea and the United States. She has recently shown work at SOMA Artspace (Berlin),

Meinblau Projektraum (Berlin), AHL Foundation (New York), MiA Collective Art, (New York) and Museum für Asiatische Kunst (Berlin). A new installation, dealing with death ritual and the afterlife will be featured at the Pacific Asia Museum,

University of Southern California and she is currently preparing for a solo exhibition at the Paul Robeson Galleries at Rutgers University.

www.estherka.com

1 Merriam-Webster Dictionary, “genealogy,” accessed September 21, 2019, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/genealogy.

2 kate-hers RHEE (@studiolo_estherka), Instagram post, August 23, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CS6TekUAEB-/.

3 kate-hers RHEE, “Transkoreaning Contracts and Calling Cards,” accessed September 19, 2021, http://www.estherka.com/contracts/.

4 kate-hers RHEE, “Transkoreaning,” accessed September 19, 2021, http://www.estherka.com/trans-koreaning/.

5 kate-hers RHEE, personal correspondence with author, September 2, 2021.

6 Ibid.

7 Claire Jean Kim, “The Racial Triangulation of Asian Americans.” Politics & Society vol. 27, no. 1 (March 1999) 105–138.

8 Ibid., 106.

9 kate-hers RHEE, personal correspondence with author, August 16, 2021.

10 RHEE, “Transkoreaning,”

11 kate-hers RHEE, “Entry# 131209: A feminist’s struggle to claim cultural identity without becoming a Mrs.,” accessed September 19, 2021, http://www.estherka.com/cms/2013/12/entry-27.html.